When recursion may not be the right answer

/ 5 min read

Last Updated:

In math, the Fibonacci sequence is a set of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones. The series goes like this:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, …

We can express this as a function F, where:

F0 = 0

F1 = 1

F2 = 1

F3 = 2

F4 = 3

F5 = 5

F6 = 8

F7 = 13

and so on. The value of the Fibonacci number F7 is F6 + F5, i.e. 8 + 5 = 13. This checks out. But look at it- this is a problem just made to be solved via recursion! Let’s write some quick JavaScript to represent this algorithm.

First let’s write a solution that uses a for loop to accomplish this. Nothing fancy for this first attempt, just a brute array. As previously stated, we can express this function as Fn = Fn-1 + Fn-2.

function fibonacci(n) {

// Instantiate our array for the first two elements of the sequence.

const sequence = [0, 1];

// Populate the array up to the element index that we need.

for (let i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

sequence.push(sequence[sequence.length - 2] + sequence[sequence.length - 1]);

}

return sequence[n];

}And then let’s write the same thing with recursion so you can see what that looks like:

function recursiveFibonacci(n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return recursiveFibonacci(n - 1) + recursiveFibonacci(n - 2);

}Wow, the problem has been simplified so much that it’s incredibly easy to understand.

Yeah, hang on. Let’s see how long these algorithms actually take to run. We can add some instrumentation statements to help us calculate the runtime of each function call.

For this, I am going to use the process.hrtime() function call in nodejs. And then let’s plot the results.

// This is an instrumentation function to help us determine how long something

// takes to run.

let start = process.hrtime();

const elapsedTime = (text) => {

// hrtime() returns an array of seconds and ns. let's convert it to ms.

const elapsed = process.hrtime(start)[0] * 1000 + process.hrtime(start)[1] / 1000000;

console.info(`${text}: ${elapsed.toFixed(3)} ms`);

// reset the clock

start = process.hrtime();

};

for (let i = 0; i <= 10; i++) {

console.log(`F${i} =`, recursiveFibonacci(i));

elapsedTime(`F${i}`);

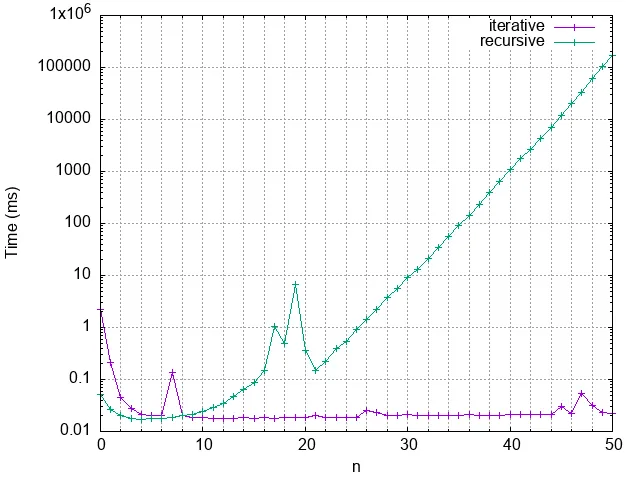

}We get some output from running this code, and it looks pretty fast. Let’s run this for a few more iterations (50 is a nice number), and because I love graphs, I’m going to plot it. I’m going to change our instrumentation function a little to return the runtime instead of printing it to the console. This way we can use something like plotter or gnuplot to graph the results of the arrays.

const runtimes = [];

for (let i = 0; i <= 50; i++) {

console.log(`F${i} =`, recursiveFibonacci(i));

runtimes.push(elapsedTime());

}It’s taking a little while to run, isn’t it. It finally finishes and let’s examine what happened. Oh no, this has all gone horribly wrong. 🤦🏾♂️

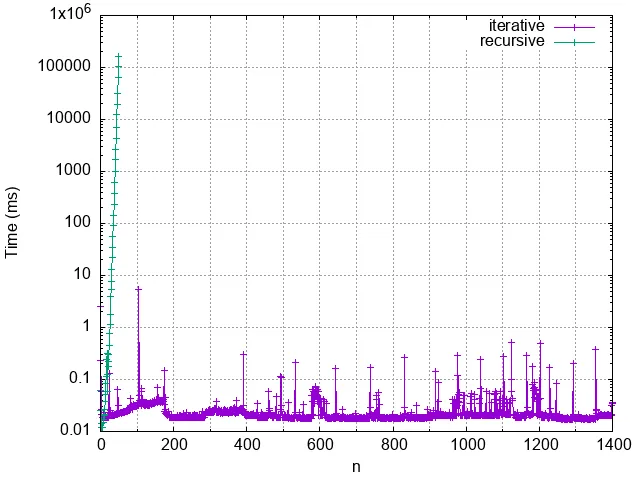

What happened here??? This is an exponential runtime. I do not like exponential runtimes. I donotlikethem. Just for fun though, let’s compare 50 recursive runs to 1400 iterative runs.

Yiiiikes, I hope you see my point.

The point however is not “don’t use recursion, recursion is bad”. Much of the issue with our recursive function is that it keeps doing the same work over and over again. To compute the 50th Fibonacci number, the recursive function had to be called over 40 billion times, and successive iterations did not have the results of the previous work done by the function. This problem of redoing the computation over and over could be mitigated if the function could only remember what it had previous computed. And that is a good segue to talking about memoization.

What is memoization?

From Wikipedia: memoization is an optimization technique used primarily to speed up computer programs by storing the results of expensive function calls and returning the cached result when the same inputs occur again.

That sounds like exactly what we want, I’ll take two. Let’s refactor our recursive function the slightest bit to cache the results of the previous work done by the function.

const memo = {};

function memoizedRecursiveFibonacci(n) {

// Is the value we want in the memo already?

if (n in memo) {

return memo[n];

}

// If we get here, this is our first time calculating this value.

let value;

if (n < 2) {

value = n;

} else {

value = memoizedRecursiveFibonacci(n - 1) + memoizedRecursiveFibonacci(n - 2);

}

// Store the results of this computation in our memo for the next iteration

// before we return it.

memo[n] = value;

return value;

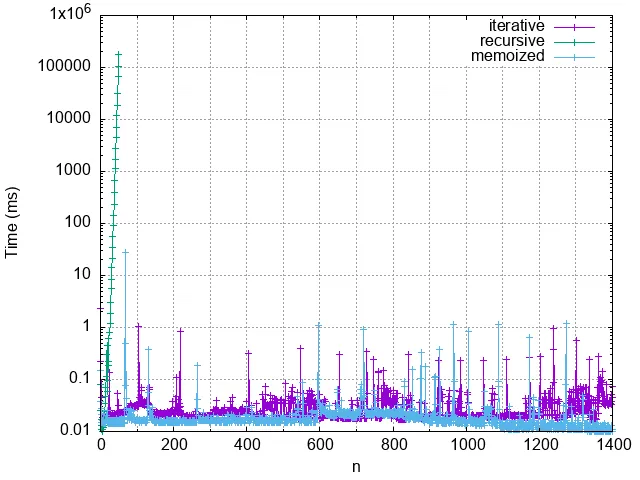

}And once again, let’s plot this against our other two implementations and see how they all compare.

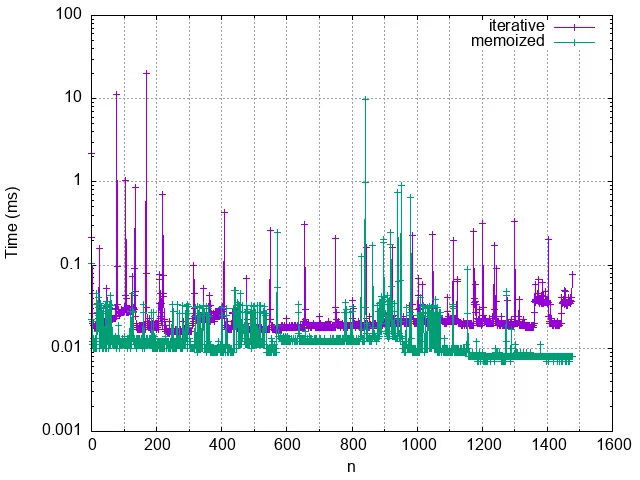

Not bad. Our memoized recursive function looks like it might even be the slightest bit faster than the iterative one. If we remove the non-memoized recursion out of this graph and plot just the other two for 1476 iterations, you can see the difference. Why 1476? Because F1477 is too big for JavaScript to handle! It will tell you that the answer is Infinity.

Recursion is an important part of functional programming and an excellent way to break up a large problem. Just be aware of the limitations and know that blindly throwing recursion at the wall is not going to work for every single thing. And remember memoization next time you face an issue of doing the same work over and over and over and over again.

All the code used for this post can be found here. The graphs used in this post were generated using usubram/nodejs-plotter which is a node module that invokes gnuplot and ps2pdf.