Zen and the art of writing good commit messages

/ 5 min read

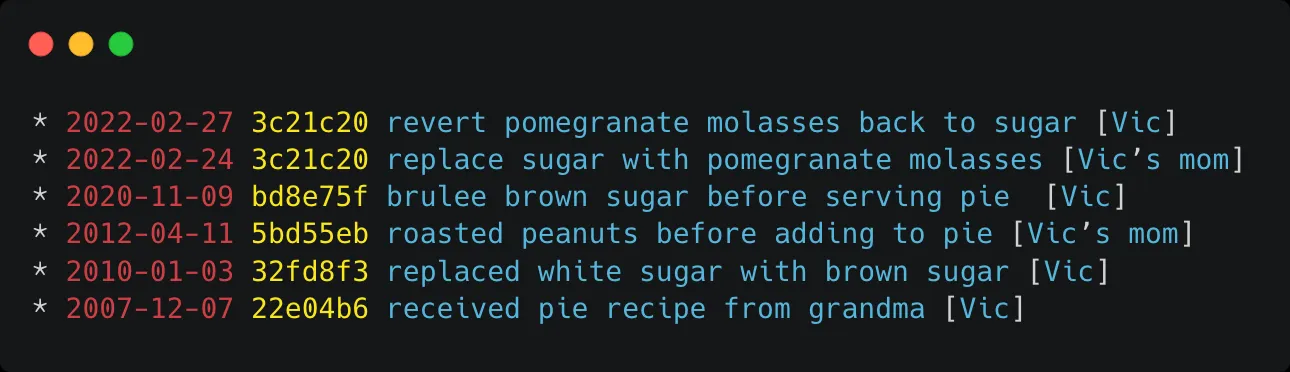

Version Control Systems (VCS) are everywhere. If you have ever used Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or Wikipedia, you have used an inbuilt version control system, sometimes known as source control or revision control. VCSes are critical in software development and are becoming more and more prevalent for very creative uses unrelated to tracking changes in code. Some examples are tracking when newspapers change their headlines or how election results arrive from polling places over time. Maybe you want to see how a particular family recipe has been tweaked and made better (or worse) over the years!

VCSes are documentation

Version control systems are a form of documentation. They allow you and your team to collaborate and make changes to your applications, and create a point-in-time bookmark of that change along with a reason for the change. This allows you to come back at a future date and see why you did something, who did it, when you did it, and which specific files in your project changed. In the event that something goes wrong, you can easily see where it was introduced and/or easily revert the change.

VCSes are supposed to help you. Use them in a manner that allows you to sleep well. Some people insist that their commit histories need to be able to tell a story of how their work changed over time. Some people…don’t.

Good and bad commit messages

A bad commit does not tell you anything useful, and forces you to do more work than you need to.

* 2021-11-27 bde060a fixed it

Source: this absolutely hilarious tweet by Louie Bacaj

What did you fix? Why? The investigator is now going to need to git show this commit and dig through your code to see what was fixed.

People should be able to look at a commit and immediately see what the general outline of a change was, and why, without going through the changeset line by line and trying to figure out what changed. People come and go, and institutional knowledge leaves with them. Leave behind a legacy with your commit messages.

A good commit message is generally a short one line description of the change you made, followed by a rationale of why you made the change. The short one-liner usually appears in places like GitHub and BitBucket as the title for your commit, and people can click into it to see the details.

There’s even a specification for it!

Conventional Commits are a specification to add human and machine readable meaning to commit messages. The conventional commits standard states that commit messages should be structured as:

<type>(optional scope): <description>

[optional body]

[optional footer]For example:

feat(auth): add twitter login to signin page

we find that users prefer twitter to all other social login providers

so we're adding a login with twitter button to the auth pages. this

change requires us to add twitter client and secret keys to the

secrets vault before this is deployed to prod.

[JIRA-12345] create a login with twitter button on the signin page.

Fixes #123But you can’t just put anything as a type. The common types are: build, chore, ci, docs, feat, fix, perf, refactor, revert, style, and test. (You can edit these according to your preferences, but I don’t.)

This is a really easy standard to follow. Moreover, I find that it discourages me from sending over large commits that are both a new feature and a bug fix, for example.

Trust, but verify

My philosophy with a lot of tooling is to make a coding/linting rules really easy to follow, but verify that the rule is not being broken.

I enforce this with a tool called commitlint, and its associated config.

Here’s how you set it all up.

❯ npm i -D "@commitlint/cli" "@commitlint/config-conventional"You can put the config for commitlint in many different places, but I like to put it in my package.json file (in JavaScript / nodejs applications).

"commitlint": {

"extends": [

"@commitlint/config-conventional"

],

"rules": {

"subject-empty": [

0,

"never"

]

}

}Let’s test that commitlint is correctly set up.

❯ echo "foo: bar" | npx commitlint

⧗ input: foo: bar

✖ type must be one of [build, chore, ci, docs, feat, fix, perf, refactor, revert, style, test] [type-enum]

✖ found 1 problems, 0 warnings

ⓘ Get help: https://github.com/conventional-changelog/commitlint/#what-is-commitlintParty time. But how do we make sure this convention is enforced when I am committing code automatically? For this I use a tool called Husky which helps me manage my git hooks.

Set up Husky

You can pretty much follow the recommended automatic installation guide on the Husky project page.

From an existing project:

❯ npx husky-init && npm install

husky-init updating package.json

setting prepare script to command "husky install"

husky - Git hooks installed

husky - created .husky/pre-commitWe don’t want that pre-commit script because it will try to run npm test, which our project does not have. Let’s delete it and create our first hook.

❯ rm .husky/pre-commit

❯ npx husky add .husky/commit-msg 'npx --no-install commitlint --edit $1'

husky - created .husky/commit-msgIMPORTANT: open up the .husky/commit-msg file and confirm that your $1 made it in there. Sometimes, depending on your terminal, this can end up being blank.

Stage and commit all your files. This will be a good test of whether your husky and commitlint installs worked.

❯ git add . && git commit -m "foo: bar"

⧗ input: foo: bar

✖ type must be one of [build, chore, ci, docs, feat, fix, perf, refactor, revert, style, test] [type-enum]

✖ found 1 problems, 0 warnings

ⓘ Get help: https://github.com/conventional-changelog/commitlint/#what-is-commitlint

husky - commit-msg hook exited with code 1 (error)Let’s commit that again, with a valid commit message, and see that our commit is not rejected.

❯ git add . && git commit -m "chore: implement husky and commitlint"🥳🥳🥳 party time.